Europe’s reusable rocket push explained: Themis demonstrator, Prometheus methalox engine, test strategy, and operational impact

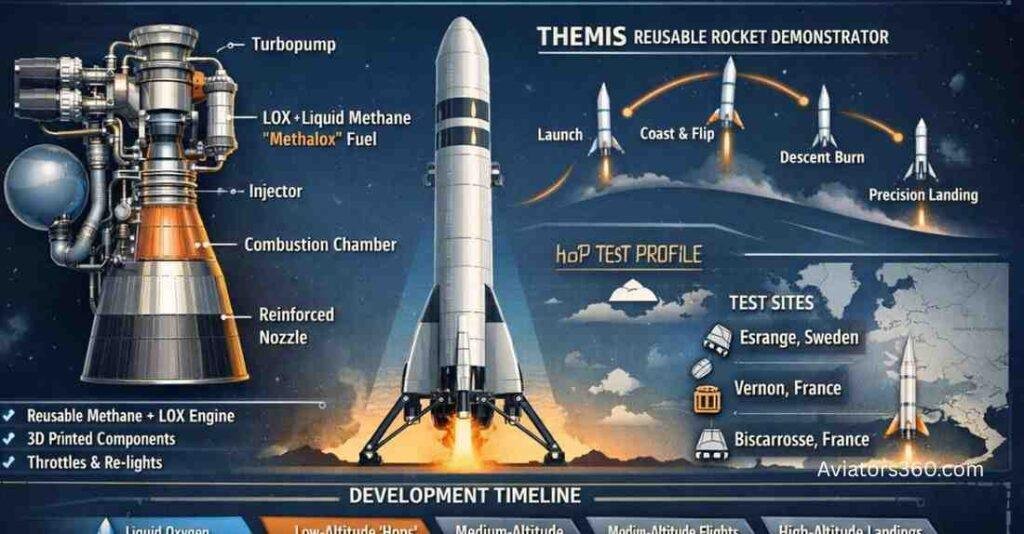

Europe is entering a new phase in its spaceflight journey. After decades of building powerful but single-use launch vehicles, European engineers are now testing whether rockets can fly, land, and fly again. At the centre of this shift are two closely linked programmes: Themis, a reusable rocket-stage demonstrator, and Prometheus, a new low-cost methane rocket engine.

Together, they represent Europe’s most serious effort yet to master reusable launch technology. The goal is not just technical success, but a long-term change in how European rockets are designed, operated, and maintained.

This article explains what Themis is, why it matters, how the Prometheus engine works, how the test programme is structured, and what all of this could mean for the future of European launchers and the aerospace workforce.

Why Europe Needs Themis

For many years, Europe’s launch strategy focused on reliability and performance rather than reuse. Launchers such as Ariane 5 and its successor Ariane 6 were designed to place satellites precisely into orbit, but their main stages were discarded after each flight.

Meanwhile, reusable rockets elsewhere began to demonstrate a different model: recover the first stage, inspect it, refuel it, and launch it again. Reuse changes the economics of spaceflight by shifting costs away from building new hardware for every mission and toward operations, inspection, and maintenance.

Europe’s response is Themis. The programme exists to answer a practical question: can Europe land a large rocket stage safely and reuse it at a cost that makes sense? Instead of jumping straight to an operational launcher, engineers are first flying a full-scale test vehicle to learn what actually works.

What Is Themis?

Themis is a technology demonstrator, not a commercial rocket. It is being developed under the leadership of the European Space Agency with ArianeGroup as the prime industrial contractor.

The vehicle represents a reusable first stage similar in size and function to those used on orbital launchers. Its sole purpose is to test technologies needed for vertical take-off and vertical landing, often shortened to VTVL.

Planned Themis configurations

Several versions of Themis are planned:

- Early single-engine demonstrators for low-altitude hop tests

- Evolved versions with improved avionics and landing systems

- Later multi-engine configurations closer to an operational booster

The programme focuses on systems that must survive repeated flights: engines, fuel tanks, landing legs, guidance software, and ground operations.

What Themis Is Designed to Prove

Themis aims to answer four core questions.

First, can a large rocket stage descend in a controlled way and land upright with high precision?

Second, can its engine restart reliably after ascent and throttle smoothly during landing?

Third, how much wear and fatigue do structures and engines experience when reused?

Finally, how long does it take to inspect, repair, and prepare the stage for the next flight?

The answers to these questions will shape future European launch vehicles.

The Test Campaign: From Hops to Higher Flights

Themis testing is centred at the Esrange Space Center in northern Sweden. Esrange offers wide, sparsely populated test areas and long experience with experimental aerospace programmes.

Themis flight-test strategy

The flight plan is gradual by design:

- Low-altitude hop tests validate basic stability, thrust control, and landing accuracy

- Higher and longer flights expand the aerodynamic and thermal envelope

- Repeated flights test reusability rather than one-time performance

Each test feeds data back into design updates for the vehicle and its engine.

Prometheus: The Engine Behind Themis

At the heart of Themis is Prometheus, a new rocket engine family developed specifically for reuse and low cost. Prometheus burns liquid oxygen (LOX) and liquid methane, a combination often called methalox.

Unlike older European engines that prioritised maximum efficiency, Prometheus was designed with a different mindset: acceptable performance, but much lower cost and easier reuse.

Why Methane?

Methane sits between hydrogen and kerosene in terms of properties.

Compared with hydrogen, methane is denser and easier to store, allowing smaller tanks. Compared with kerosene, methane burns much cleaner, leaving far less soot inside the engine. That matters for reuse, because cleaner engines need less inspection and cleaning between flights.

Methane engines are also well suited to deep throttling, which is essential for controlled landings.

Prometheus Engine Design Philosophy

Public information about Prometheus emphasises simplicity rather than cutting-edge complexity. The engine uses a combustion cycle chosen to minimise part count and ease manufacturing, even if that means slightly lower peak efficiency.

Core Prometheus design principles

The key ideas behind Prometheus include:

- Throttleability, allowing smooth control during landing

- Reliable re-ignition, even after exposure to high temperatures

- Modular design, so parts can be inspected or replaced easily

The engine has been tested extensively on the ground, including multiple hot-fire runs and restart sequences.

Manufacturing Prometheus for Low Cost

One of the most important features of Prometheus is how it is built.

Large portions of the engine are produced using additive manufacturing, commonly known as 3D printing. This allows complex internal cooling channels and shapes to be made as single pieces rather than assemblies of many parts.

Benefits of additive manufacturing

Fewer parts mean:

- Shorter production times

- Lower assembly costs

- Fewer failure points

The long-term goal is to reduce engine cost by an order of magnitude compared with earlier European engines.

How Vertical Landing Works

Landing a rocket stage is a carefully choreographed sequence.

After ascent, the stage follows a short coast phase. It then reorients itself for descent and begins atmospheric entry. As it approaches the ground, the engine restarts and throttles down to reduce vertical speed.

In the final seconds, landing legs deploy, the engine performs a controlled braking burn, and the vehicle touches down vertically.

This entire process depends on precise guidance, navigation, and control systems working together in real time.

Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GNC)

GNC is the “brain” of a reusable rocket.

Navigation systems combine data from inertial sensors, satellite positioning, pressure sensors, and radar altimeters. Guidance software calculates where the vehicle should be at every moment. Control systems then adjust engine thrust and direction to follow that path.

Themis flights provide crucial real-world data to fine-tune these systems, especially under wind and atmospheric disturbances.

Landing Legs and Structural Design

Landing legs may look simple, but they are a major engineering challenge. They must be light enough not to reduce payload capacity too much, yet strong enough to absorb landing loads repeatedly.

Engineers must balance safety margins against mass penalties. Themis tests help determine how robust these structures need to be for routine reuse.

Ground Operations and Maintenance

Reusable rockets move much of their cost from manufacturing to operations.

After each flight, the stage must be inspected, refuelled, and prepared again. Engineers are studying which inspections are truly necessary and which can be simplified or automated.

Key inspection areas

- Engine turbomachinery

- Fuel tank welds

- Landing leg attachment points

- Avionics and control systems

The aim is to make rocket maintenance closer to aircraft maintenance, with predictable schedules and standard procedures.

How Themis Feeds Future European Launchers

Themis is closely linked to Europe’s next-generation launcher concepts, including Ariane Next.

Rather than committing to full reuse immediately, decision-makers will use Themis data to judge whether reuse provides real economic benefits.

If refurbishment times and costs are low, a reusable booster becomes attractive. If not, Europe may choose partial reuse or other hybrid designs.

Risks and Open Questions

Several challenges remain.

Precision landings must work reliably in varying wind conditions. Engines must restart flawlessly after repeated thermal cycles. Structures must withstand fatigue without becoming too heavy.

Perhaps the biggest unknown is cost. Reuse only makes sense if savings from flying again exceed the cost of extra mass, infrastructure, and maintenance.

What This Means for Aerospace Professionals

For engineers and technicians, reusable rockets change job profiles.

Skills in inspection, non-destructive testing, additive manufacturing, and cryogenic systems become increasingly important. Launch operations begin to resemble airline ground handling, with tight schedules and rapid turnaround.

As reusable launchers mature, demand will grow for specialists who can bridge aerospace engineering and operational maintenance.

Conclusion: A Quiet but Profound Shift

Themis and Prometheus do not aim to make headlines with spectacular launches. Their purpose is more fundamental. They are about learning, measuring, and understanding what it really takes to reuse a rocket stage in Europe.

If the programme succeeds, it will shape the design of future European launchers and redefine how spaceflight is organised and paid for. If it falls short, it will still provide valuable data that prevents costly mistakes later.

Either way, Themis represents a turning point: Europe is no longer asking whether reusable rockets are possible, but whether it can make them practical, affordable, and sustainable on its own terms.

Disclaimer :

This blog is intended for general informational and educational purposes only. The content is based on publicly available information, industry reports, and open-source references available at the time of writing. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and clarity, details related to space programmes, technologies, timelines, and performance parameters may change as official projects evolve.

This blog does not represent official statements, positions, or endorsements of the European Space Agency (ESA), ArianeGroup, or any associated organisations. Technical descriptions are simplified for reader understanding and should not be interpreted as complete engineering specifications or authoritative program documentation.

The publisher and author do not accept liability for any errors, omissions, or outcomes arising from the use of this information. Readers are advised to consult official sources and technical publications for the most current and authoritative details regarding Themis, Prometheus, or related European launch programmes.